The Continuing Effort to Deny that Libertarian‐ish Voters Exist

David Boaz

Here we go again. David Leonhardt of the New York Times dredges up a poorly designed chart from 2017 that purported to show that there are very few “fiscally conservative, socially liberal” American voters. At the time Karl Smith pointed out some basic design flaws in the analysis. Emily Ekins noted that determining the number of liberal, conservative, libertarian, and populist/communitarian/statist voters depends very much on the definitions you start with and the issues you choose. She concludes: “The overwhelming body of literature, however, using a variety of different methods and different definitions, suggests that libertarians comprise about 10–20% of the population, but may range from 7–22%.”

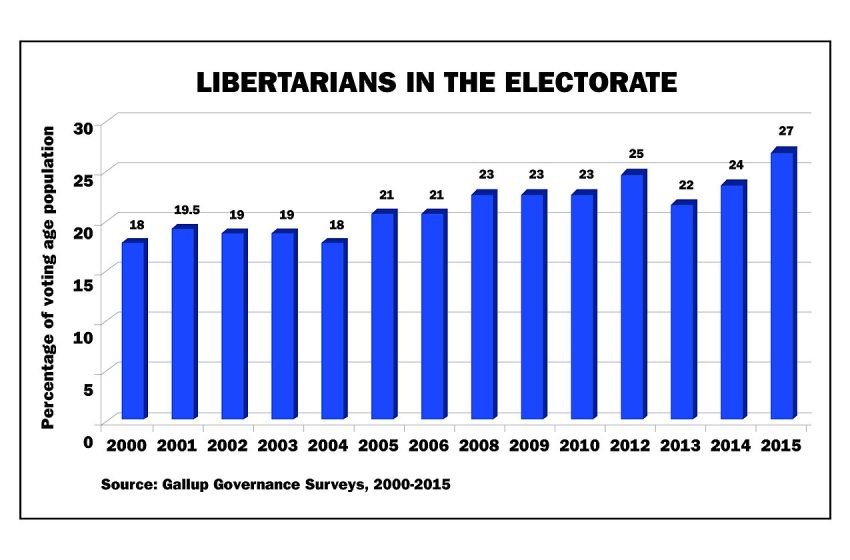

The Gallup Poll has regularly used a two‐question screen to divide voters into four ideological categories, and they typically found libertarians around the 20 percent mark.

Beginning in 2006 David Kirby and I used a three‐question screen to identify libertarians, and we found that with that stricter definition “libertarians” constituted about 13 percent of the population and 15 percent of reported voters. And note that if we insisted on agreement with the liberal or conservative position on all three questions, the number of liberals and conservatives would likely be quite a bit lower than 25 percent.

It’s quite possible, of course, that the Trump Effect on Republican voters, not to mention the anti‐Trump backlash among independent and Democratic voters would have significantly changed some of these pre‐Trump, “normal” findings.

We also commissioned Zogby International to ask our three American National Election Studies questions to 1,012 actual (reported) voters in the 2006 election. We asked half the sample, “Would you describe yourself as fiscally conservative and socially liberal?” — the very categorization Leonhardt used in his column. We asked the other half of the respondents, “Would you describe yourself as fiscally conservative and socially liberal, also known as libertarian?”

The results surprised us. Fully 59 percent of the respondents said “yes” to the first question. That is, by 59 to 27 percent, poll respondents said they would describe themselves as “fiscally conservative and socially liberal.”

The addition of the word “libertarian” clearly made the question more challenging. What surprised us was how small the drop‐off was. A healthy 44 percent of respondents answered “yes” to that question, accepting a self‐description as “libertarian.” We summed all that up in this handy graph:

Leonhardt and others may well be right that there are more “socially conservative, fiscally liberal” voters than “fiscally conservative, socially liberal.” Though the latter are better educated, more affluent, and more likely to vote. And in any case the numbers are a lot closer than Leonhardt and his befuddled chart would have you believe. Also, much depends on the questions you ask. Kirby and I used broad philosophical questions, as did Gallup, Pew, and ANES. But you can also use specific issues, as did a Washington Post poll. The combination “abolish Medicare” and “repeal all drug laws” would find a huge percentage of SCFL voters and very few FCSL or libertarianish voters. “Gay people should be able to get married” plus “the government spends too much money” will get you a lot of FCSL voters. Which one is closer to actual American policy conflicts?

There’s plenty of room for debate about how to analyze the ideological positions of American voters. But looking at the available data is a good place to start.