For Spending Cuts, How about the EDA?

Chris Edwards

The recent debt‐ceiling deal put caps on discretionary spending for 2024 and 2025. But House conservatives want larger reforms and are seeking additional cuts in fiscal 2024 appropriations bills. House Appropriations Chair Kay Granger is right that “the debt ceiling bill set a ceiling, not a floor” for 2024 spending.

What should the GOP cut? One place to look is appropriations that are “unauthorized.” Federal discretionary programs are supposed to be authorized before appropriators spend, but authorizations have lapsed for many programs and Congress spends anyway. Romina Boccia argues that this rise in “zombie spending” reduces oversight and increases waste.

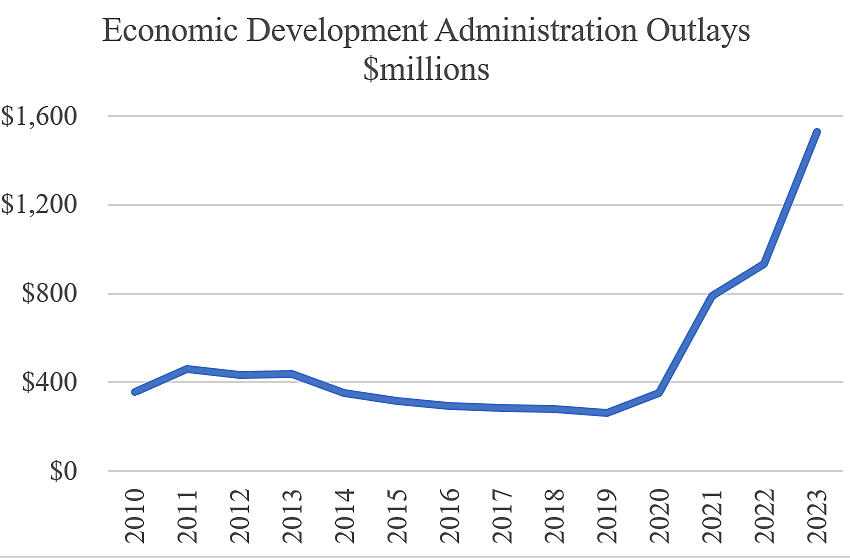

Consider the Economic Development Administration (EDA), which hands out hundreds of millions of dollars a year in subsidies to state and local governments and the private sector. EDA spending has soared from $264 million in 2019 to $1.53 billion in 2023, as shown in the figure. The EDA budget received a boost from recent legislation including the American Rescue Plan and CHIPS acts.

EDA spending authorization lapsed after 2008. The last serious attempt to reauthorize it was in 2011, which failed in the Senate by a 49 to 51 vote. Supporters at the time touted such things as, “For every dollar spent in EDA, $7 of private investment is attracted,” as Senator Barbara Boxer suggested. But opponent Senator Tom Coburn said that such claims were anecdotal and made up by the EDA and grantees themselves. He pointed to the lack of rigorous analysis of EDA spending and opined that the agency “has been used as a congressional slush fund to direct money to friends of Members of Congress.”

The EDA was created in 1965 and says its role is to “lead the federal economic development agenda.” The agency sprinkles grants widely to congressional districts across the nation in a vast range of activities. EDA leaders make lofty claims about jobs and investment that are not sufficiently challenged by members of Congress, who are eager to secure grants for their districts.

Cato has critiqued the EDA, and federal auditors have been skeptical about some of the agency’s claims. The Government Accountability Office testified that the EDA’s reliance on grantee estimates “may lead to inaccurate claims about program results.” Analysts have long noted the “gulf between promise and performance” at the EDA.

What sorts of things does the EDA fund? The following are some projects highlighted in EDA annual reports from 2018 to 2021 (see here) that fit into two categories: 1) projects that, if useful, should have been funded by the states, and 2) projects that, if useful, should have been funded by the private sector.

Should have been funded by the states:

$8,350,057 to improve the International Parkway Bridge in Tracy, California (2021).

$7,899,000 to make levee upgrades in Hamburg, Iowa (2020).

$5 million to renovate the University of Texas Coastal Ocean Science building (2019).

$1,975,800 to Delaware Technical and Community College for a skills training facility (2018).

$3,806,761 for a new generator at the University of South Alabama (2021).

Should have been funded by the private sector:

$2,546,760 to the Institute for Advanced Learning and Research to purchase equipment for training employees (2021).

$10,214,022 for Leon County Research and Development Authority to build a business incubator in Tallahassee (2020).

$7,872,090 to Blue Lake Rancheria, California, to build a local business incubator (2019).

$2,030,000 to help Cedars‐Sinai Biomanufacturing Center purchase equipment (2018).

$1,996,160 to purchase equipment for training at the Fairbanks Pipeline Training Center Trust (2021).

The EDA does not have special skills for boosting economic growth that the states and private sector do not have. Federal funding of local industrial parks, incubators, equipment, and other items just adds bureaucracy. Taxpayers pay for the federal EDA bureaucracy of more than 300 employees, and then those folks impose rules and regulations on local partners, which further raises costs. To receive EDA funding, for example, regions must complete central‐planning‐style “Comprehensive Economic Development Strategies.”

The EDA often claims that it garners high returns on projects, but if true we would not need the agency because the states and private sector would eagerly fund such projects. In other cases, the EDA says that it is filling unmet needs. The head of EDA testified that “without the support and funding of EDA, many projects would struggle to attract necessary capital.” But maybe those projects struggle because they have poor management or are economic losers.

Another problem with EDA projects is that they can pit jurisdictions against one another in a zero‐sum game. In his study of the EDA, David Bier says that the agency gave $2 million to Visalia, California, to expand an industrial park, but then that subsidy induced a medical equipment manufacturer to relocate hundreds of jobs from elsewhere within the state. In such cases, EDA subsidies create winners and losers and probably no net value.

The EDA is one of many programs that spread federal subsidies around the country for local development. But local areas needing development can reform their own taxes and regulations to spur entrepreneurship and private investment. Jurisdictions that create inviting climates for businesses and skilled workers can prosper without subsidies.

Federal funding of local projects is inefficient for many reasons, and it is not affordable given ongoing federal deficits of more than $1.5 trillion a year. Both the Reagan and Trump administrations proposed eliminating the EDA. House Republicans should take another shot at reform.