Wasn’t Lower Inflation Supposed to Be Impossible without Higher Unemployment?

Alan Reynolds

A paper on “Managing Disinflation” was recently presented at Chicago Booth by former Fed Governor Frederic Mishkin, and four distinguished co‐authors. “There is no post‐1950 precedent for a sizable central‐bank induced disinflation,” they concluded, “that does not entail substantial economic sacrifice [unemployment] or recession.”[1] That was, of course, cheerleading for the familiar “Phillips Curve” theory, which claims low inflation causes high inflation by raising wages, so high inflation can only be reduced by higher unemployment.

The Phillips Curve is the heart and soul of the Federal Reserve’s forecasting model. It is the reason Fed Chair Powell keeps fretting about “tight labor markets” as the reason the FOMC can never stop pushing short‐term interest rates above long‐term rates until another “hard landing” pushes the unemployment rate above 4.5 percent.

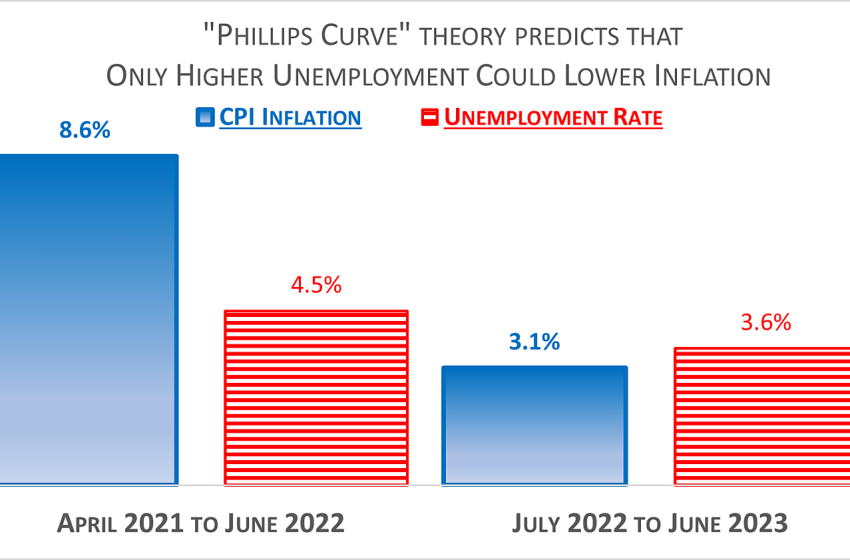

According to the “Managing Disinflations” and endless lectures by Fed officials, the reduction of inflation since last June could not have happened. After 15 months in which the CPI inflation rate averaged 8.5 percent (and the fed funds rate was tiny), it has now fallen to 3.1 percent for 11 months. Did that happen because the unemployment rate went up? On the contrary, unemployment fell from 4.5 percent to 3.6 percent.

But the Fed and academic economists are not easily dissuaded by troublesome facts. They just keep on searching for new ways of explaining why the theory is still right, but the world has gone wrong.

[1] Stephen G. Cecchetti, Michael E. Feroli, Peter Hooper, Frederic S. Mishkin, and Kermit L. Schoenholtz. “Managing Disinflation” (February 2023) Table 2.1. https://www.chicagobooth.edu/-/media/research/igm/docs/usmpf-2023-confe…