American Compass Dystopia: Finance’s “Disproportionate Share” Of Profits

Norbert Michel and Jai Kedia

A few weeks ago, American Compass released Rebuilding American Capitalism, A Handbook for Conservative Policymakers. This Forbes column (American Compass Points To Myths Not Facts) provided a very brief critique of the handbook’s “Financialization” chapter, and Oren Cass, American Compass’s Executive Director, released a response titled Yes, Financialization Is Real.

This Cato at Liberty post is the third in a series that expands on the original criticisms outlined in the Forbes column. (The first and second in the series are available here and here.) This post demonstrates that the evidence does not support American Compass’s claims regarding profits. This post also documents American Compass’s failure to clearly specify terms and dates, as well as its selective use of examples that appear to support its positions.

To recap, the American Compass handbook states the following:

American finance has metastasized, claiming a disproportionate share of the nation’s top business talent and the economy’s profits, even as actual investment has declined.” [Emphasis added.]

The original critique in Forbes pointed out: “It’s impossible to know exactly what American Compass means by profits because they don’t cite anything, but the National Income and Product Accounts provide financial and nonfinancial company profits dating back to 1998.” With nothing else to base an analysis on, the critique then summarized the NIPA data, stating:

While the annual share of total corporate profits in the NIPAs has varied, at the end of 2022 it was 18 percent for financial companies versus 82 percent for nonfinancial companies. In 1998 the share for financial firms was a touch higher (20 percent) compared to nonfinancial firms (80 percent).

The original Forbes critique didn’t make clear, however, that these respective shares do not suggest either sector “claimed” a share of total available profits at anyone’s expense. They’re merely part of the Bureau of Economic Analysis’s national accounting exercise that estimates the value of all final goods and services produced in the United States. There is nothing inherently wrong with a higher (or lower) profit share in either sector.

In his response, Cass points out that the NIPA data goes back to 1929. He then shows that the share of total corporate profits for financial firms is twice as high in the 2010s versus in the 1950s (using 10‐year averages for each decade), and finally complains that the original critique’s “focus on the 2022 data as the endpoint is unfortunately misleading.”

While Cass still neglects to specify any kind of preferred profit metric, fails to explain why his use of 10‐year averages for each decade between 1950 and 2019 is appropriate, and fails to stipulate what the optimal share of profits should be, at least he acknowledges the NIPA data goes back to 1929. (For the record, it is just as misleading for American Compass to focus on 1950 to 2019 as evidence of an increase in the financial sector share as it would be for us to focus on the decline since 2009 as evidence of a decrease.)

While it is true, as Cass states, that the financial sector share was 28 percent in 2019, it is also true that the series exhibits a high degree of volatility. The standard deviation of the full series is about seven percentage points, and the financial sector share peaked at an unusually high value in 2002 (37 percent) before crashing to an unusually low value in 2008 (8 percent). This high degree of volatility makes it especially important to focus on the long‐term trend rather than on any specific period.

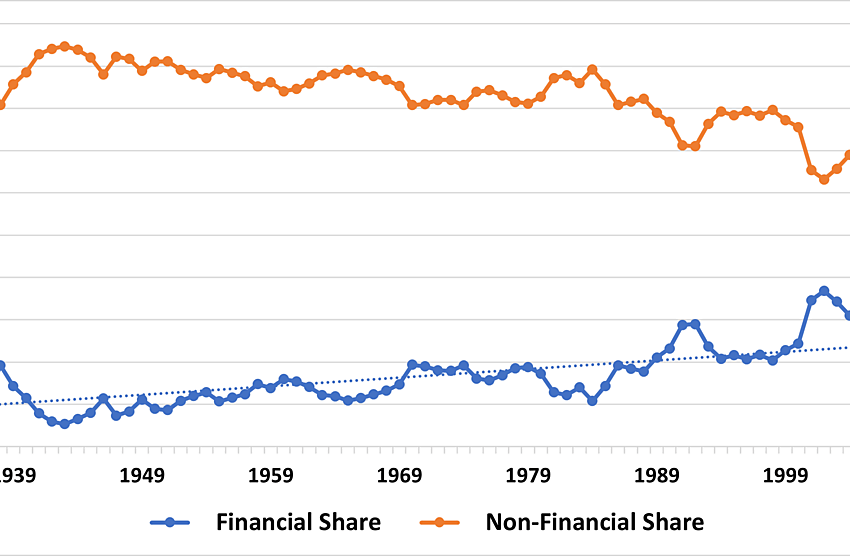

As Figure 1 demonstrates,[1] using the NIPA data, the long‐term trend for the financial sector’s share of total corporate profits increases slowly throughout the roughly 100‐year period. The slope of the trend line in Figure 1 indicates the financial sector’s share of corporate profits increased by about 0.2 percent per year between 1929 and 2022.

But that’s all the series reveals. It does not provide evidence that the financial sector “claimed” a “disproportionate share” of the economy’s profits, much less that this rate of change harmed the broader economy.

Importantly, it is not the case that corporate profits in the non-financial sector have been falling throughout this period. That is, even though the financial sector’s share of NIPA corporate profits has been slightly increasing for 100 years, profits in the non‐financial sector have been steadily growing, as has the broader economy.

Figure 2 provides a similar analysis. It shows that financial sector profits as a share of GDP have averaged less than two percent from 1929 to 2022. The series exhibits a slightly increasing trend, rising about 1.5 percentage points throughout the period, with a recent downtick since the early 2000s. While it would be misleading to claim that this recent downtick demonstrates a major failure of capitalism, selectively fixating on a narrow period to draw incorrect inferences mirrors American Compass’s approach to other claims it has made.

For instance, in The Rise of Wall Street and the Fall of American Investment, American Compass claims that corporate profits have stagnated. Sort of. For instance, the report states:

Corporate profits from domestic industries fell for four straight years, from 2014 to 2018, even as the stock market was surging. The level in 2018–19 was 11 percent lower than at the prior business cycle’s peak in 2005-06.

The report then presents a graph of pre‐tax real corporate profits from 1998 to 2019, titled Profits Stagnating. The graph displays a very clear upward trend for the full period, but the report only discusses the decline in the level of profits from 2014 to 2018, and the level of profits in 2018 and 2019 relative to the peak in 2005 and 2006. In other words, American Compass’s claim that corporate profits have stagnated ignores the broader trend and relative measures of profits, and carefully selects periods for comparison.

The above examples demonstrate American Compass’s propensity to pick and choose metrics and time periods that appear to provide evidence for its claims. But, overall, these statistics do not provide evidence that “In recent decades, American finance has metastasized, claiming a disproportionate share of…the economy’s profits.” Of course, if American Compass has an optimal share for the financial sector in mind, it should clearly explain what that number is and why it is optimal.

In the next post, we will discuss claims involving “financialization’s” alleged effect on investment.

[1] The figure omits data for 1932 and 1933 as these values, during the Great Depression, turned aggregate corporate profits negative. For the sake of completeness, the numbers are presented here. In 1932 and 1933, corporate profits are -$0.2 billion in each year, financial firms’ profits are $0.6 billion and $0.8 billion respectively, and non‐financial firms’ profits are -$0.8 billion and -$1 billion respectively.