Do the Presidential Candidates Like the Constitution, or Just the Idea of it?

Anastasia P. Boden

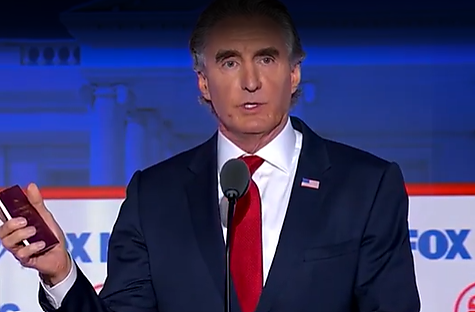

The Constitution literally made an appearance at the first Republican presidential debate last Wednesday. When Doug Burnham was asked whether he supported a federal abortion ban, the pro‐life governor whipped out his pocket Constitution and waved it around in the air, noting that whatever his policy preferences, he believes enacting a federal ban is beyond Congress’s enumerated powers. This was the first of nearly two dozen times the candidates mentioned the Constitution.

But for all of their claims of fidelity to the Constitution, the candidates sure got a lot wrong about it. Vivek Ramaswamy, for instance, said in his closing remarks that the Constitution (ratified in 1788), is “what won us the American Revolution” (which ended 5 years earlier, in 1783). A slip of memory, perhaps, but it was notable given his suggestion that the voting age be raised to 25 for 18‐to 24‐year‐olds that can’t pass a civics test. It’s also notable that such a voting requirement would violate the 26th Amendment.

For his part, Ron DeSantis emphasized Florida’s dedication to teaching constitutional history in schools, but many of his own measures have lost against constitutional challenges. The governor has garnered a reputation for reining in “wokeness,” but in furtherance of that goal some of his actions have sacrificed private businesses’ and individuals’ constitutional freedom to make their own choices. Courts have enjoined his ban on vaccination requirements as applied to private cruise lines, his ban on private social media companies’ ability to moderate user content, and provisions of the STOP WOKE Act that prohibit discussion of Critical Race Theory in universities and private businesses.

The most glaring misapprehension the candidates had about the Constitution was its limits on their own power should they become president. Take their remarks on the administrative state. Many candidates supported scaling back the myriad agencies that govern everything “from gas stoves to Greek yogurt” largely free of congressional (and sometimes even executive) oversight. Ramaswamy, for example, said “[t]he only war that I will declare as US President will be the war on the federal administrative state that is the source of those toxic regulations acting like a wet blanket on the economy.” Asa Hutchinson used similarly war‐laden language, pledging “to reduce … 10 percent our federal nondefense workforce. That’s a specific pledge … that attacks the administrative state.”

Reducing the administrative state is a pro‐Constitution sentiment. Federal agencies often unconstitutionally wield the powers of all three branches, making rules and regulations, enforcing them against violators, and adjudicating guilt before in‐house judges. And when individuals go to court to challenge the agencies’ power, deference doctrines require judges to defer to the agencies’ interpretations of statutes and regulations—even if there’s an objectively better interpretation. In short, administrative agencies now act as judge, jury, and executioner, in violation of the Constitution’s promise of separation of powers.

But what can the president do about any of this? A few of the candidates seem to think they can simply get rid of entire departments with a snap of their fingers. Ramaswamy, DeSantis, Burgum, and Pence all vowed to abolish the Department of Education. But even assuming the DOE or other agencies are unconstitutional or a bad idea, there are limits on the president’s ability to scale them back. A president could refuse to make appointments, get rid of executive department‐created boards, spend less than Congress has appropriated (through a process called “rescission”), or eradicate specific abusive practices, but they’ve historically sought authority to make more sweeping changes to agencies and departments via reorganization legislation.

In other words, eliminating DOE is going to require support from Congress. Maybe what the candidates mean is that they’d seek congressional authority to eliminate various departments. But form matters.

The candidates also seemed to misunderstand the scope of presidential power when they suggested they’d invade Mexico as a response to rising opioid abuse, which they blame on Mexican cartels. DeSantis said he’d “send troops” into Mexico to take out fentanyl labs and drug cartel operations. Pence referred to “partner[ing] with the Mexican military” to “hunt down and destroy the cartels.” And Ramaswamy, Hutchison, and Tim Scott all alluded to using military resources to stop the flow of fentanyl at the border.

The president can’t just invade other countries. Congress, not the president, has the power to make or declare war. As James Madison wrote, “In no part of the Constitution is more wisdom to be found, than in the clause which confides the question of war or peace to the legislature, and not to the executive department.” This allocation of powers prevents the “temptation” that would arise for one person to make such a weighty decision. “War,” he concluded, is “the true nurse of executive aggrandizement.”

The president does, however, have the power to repel attacks. Perhaps that’s why some of the candidates used language suggesting that the flow of fentanyl constitutes an “invasion” of the United States. Ramaswamy alluded to “the invasion of our own southern border,” DeSantis said he would declare the situation a “national emergency,” and Chris Christie said China was engaging in “an act of war” by sending chemicals to Mexico to be used in creating fentanyl. This is the same rhetoric the state of Texas is using to justify putting buoy‐barriers in the Rio Grande, potentially in violation of federal law and Mexican‐American treaties. But as law professor (and Cato’s B. Kenneth Simon Chair) Ilya Somin argues, neither immigration nor drug smuggling are an “invasion” in the constitutional sense.

As Justice Robert Jackson famously said, emergency powers “tend to kindle emergencies.” If the last few years have taught us anything, it’s that we should take care before calling something a crisis that requires executive intervention. Since COVID, we’ve seen politicians suggest there’s a student loan crisis, a climate crisis, a gun violence crisis, a border crisis, and a drug crisis. The president, say the candidates, can save us from all of these problems.

This is just the demagoguery our Founders were worried about and it’s why they imagined an office that would resist the “transient impulse[s] of the people,” not one that would egg those impulses on by calling everything an emergency.

The candidates aren’t the only ones with an exaggerated sense of the president’s importance in our constitutional structure. One of the debate’s moderators asked each candidate how they’d “inspire us.” But as Federalist 69 notes, compared to English monarchs, American presidents have “no particle of spiritual jurisdiction.” That is, Americans don’t need a spiritual leader. We need a president who will respect the Constitution and the modest role it creates for the federal government—including the executive.