Where Did Your Tax Dollars Go? A Federal Budget Breakdown

Romina Boccia

It’s officially Tax Day. Time to take stock.

The federal government spent $6.3 trillion in 2022. Tax dollars paid for $4.9 trillion or 78 percent. The rest (22 percent) was borrowed. Borrowing is deferred taxation, so ultimately deficit spending too will be paid for by taxes.

Where did all that money go?

The federal government spends the most on transfer programs. That is when the government redistributes money from one group to another rather than supplying governmental services like national defense.

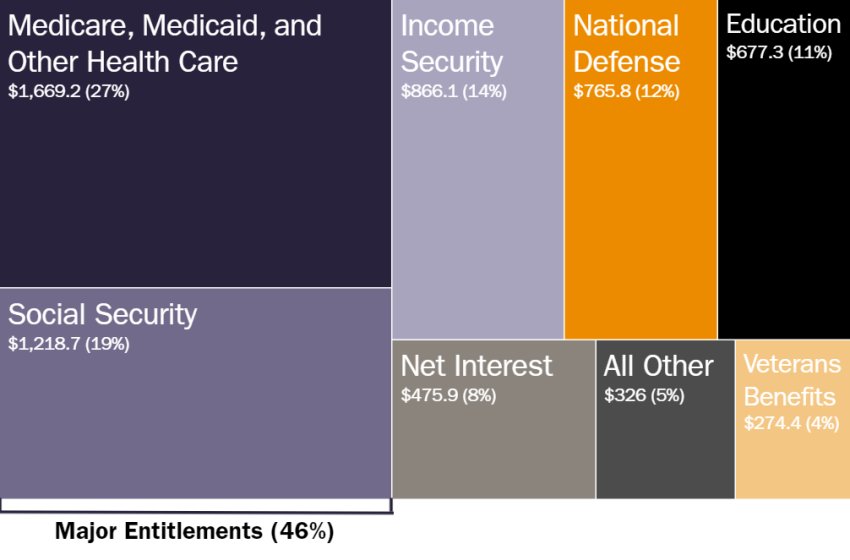

As Figure 1 below shows:

Major entitlements—Medicare, Medicaid, other health care, and Social Security—devoured nearly half of the 2022 budget, consuming 46 percent of all spending. ($2.9 trillion)

Other federal transfer programs consumed another 18 percent. “Income security” and other benefits include federal employee retirement and disability, veterans’ benefits, unemployment benefits, and welfare programs such as food and housing aid.

Overall, two‐thirds of government spending in 2022 went to pay some sort of benefit to someone. And that’s before accounting for student loan forgiveness.

Interest on the U.S. federal debt consumed 8 percent of the budget. ($476 billion)

Meanwhile, 12 percent of all federal spending went toward national defense. ($766 billion)

Most noteworthy, spending on education more than doubled compared to 2021, due to $379 billion in student loan debt forgiveness, initiated by the Biden administration.

The federal government’s budget outlook is quite dismal as well. Federal health care programs and Social Security make up 60 percent of projected spending growth over just the next 10 years. Interest costs from servicing the federal debt are projected to add 22 percent to spending growth. Combined, major entitlement programs and interest will be responsible for 82 percent of projected spending growth over the next 10 years.

Meanwhile, congressional Republicans are primarily focused on cutting and capping discretionary spending growth. They must start somewhere.

Unfortunately, if legislators continue to refuse to seriously consider health care and old age entitlement reform, there isn’t much they’ll be able to do to avoid massive middle‐class tax increases. Medicare and Social Security are responsible for 95 percent of long‐term unfunded obligations. Benefit growth is unsustainable and the alternative of doing nothing risks a future fiscal crisis. There’s simply not enough money to grab from higher‐income earners to make the math work.

And there is no way to grow out of this fiscal situation either. Social Security is indexed to grow with average wages and Medicare spending is growing faster than economic growth as the U.S. devotes an increasing share of the economic pie toward health care. As John Cogan with the Hoover Institution at Stanford University has shown, policies to limit the growth in inflation‐adjusted Social Security benefits and Medicare expenditures can play a key role in meeting the U.S. fiscal challenge.

Deficits today represent tax increases tomorrow. So, if you thought your taxes were too high and burdensome this year, I have bad news for you. Without reducing the growth in Medicare and Social Security benefits, Congress will have no choice but to raise taxes on most Americans at some point in the future.