Australians and Septic Tank Yanks

Paul Matzko

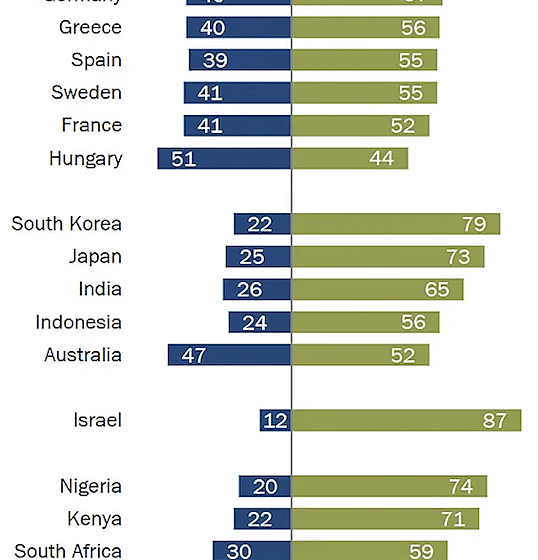

This global public opinion poll asking respondents whether they have a favorable view of the USA has been bouncing around the interwebs. The topline finding — the US is pretty popular! — surprised many American cultural critics who remember the bad old days of the Iraq War when global criticism of US imperialism surged.

I find the handful of countries where the opinion of the US remains more negative just as interesting. Hungary’s worst‐in‐Europe result is amusing given how the far Right in the US fetishizes Viktor Orban’s reactionary politics. American Hungary stans suffer from sublimated self‐hatred, wishing they could be as xenophobic and culturally chauvinist as team “Make Hungary Magyar Again.”

But the other outlier country on this list with a marked dislike of the US might be more of a surprise to Americans: Australia. We’re almost underwater Down Under. This is in sharp contrast with how highly Americans think of Australia; if you combine all positive responses from this survey, Americans consider Australia their warmest ally. Which means the gulf between how Americans and Australians view each other would be one of the widest in the world!

As it so happens, I spent eight summers as a teenager living in Australia. That certainly doesn’t make me a country expert — and it’s been two decades since I was last there — but it does mean that Australian antipathy towards the US doesn’t take me by surprise.

That dislike was very much on the surface when I was a 10 or 11 year old trying to make Aussie friends. The most popular country singer in Australia at the time was the man, the legend, John Williamson. I’ve written about Australian country music elsewhere, but I can still sing many of Williamson’s top hits from memory, including his rip‐roaring nationalist anthem “A Flag of Our Own” (1991). Williamson was a republican, which meant that he believed Australia should leave the British Commonwealth, reject the monarchy, and take the British stripes off the Australian flag. Here’s the song’s chorus:

‘Cause this is Australia and that’s where we’re from

We’re not Yankee side‐kicks or second class P.O.M.s

And tell the Frogs what they can do with their bomb

Oh we must have a flag of our own

Let me decipher that for you. P.O.M.s stands for “Prisoners of Her Majesty,” or Brits, which is often amended with an adjective such as “whingeing POMs” to describe those who yearn for ye olde country and constantly complain about Australia’s supposedly backward ways. This was a particularly popular complaint in Australia in the aftermath of Australia’s 1975 constitutional crisis. The Australian Governor‐General — a crown appointee in a mostly symbolic role — had invoked a long neglected royal power and replaced the elected left‐wing prime minister with a conservative. (For comparison, imagine the hoopla if King Charles III were to kick British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak out of office and install a Labour prime minister!)

“Frogs,” of course, are the French, who were on the radar of Aussie nationalists in the 90s for conducting nuclear testing in their Polynesian colonies — which Australia considered its own backyard — and doing so without regard for the effects of nuclear fallout on surrounding islands and Australia itself.

That leaves us with Yankees, commonly shorted to “Yanks,” which quickly becomes, via Australia’s penchant for rhyming puns, “Septic Tanks,” or then shortened further to “seppos.” (Aussies are world leaders in slang. It’s like if Cockney wasn’t just the lingo of one neighborhood in London but had been exported en masse via prison ships, transported to the other side of the globe, and then had taken over an entire continent. Oh wait…)

Maybe you’re wondering why America made that opprobrious list alongside the POMs and Frogs. We weren’t testing any nukes in the Pacific (at least, we hadn’t for a while) and we weren’t meddling in their domestic politics (though blaming the CIA for the 1975 constitutional crisis remains popular among Aussie conspiracists).

But when this song was released in 1991, the Australian military had just participated in the US‐led Gulf War. Although suffering no combat casualties, Australian nationalists saw this as yet another example of Australia blindly serving the interests of foreign superpowers, from dying at the command of callous British generals in the trenches at Gallipoli — the subject of a 1981 blockbuster starring a young Mel Gibson — to the failed fight alongside the Yanks in the jungles of Vietnam.

Bear in mind that Australia’s anti‐Vietnam War protests in 1970 were the *largest* protests in their history; by contrast, the much feted anti‐Vietnam war protests in the US don’t even crack our top 27! Australia’s involvement in the Iraq War did little to assuage critics who believed Australia should stop playing second fiddle to the US, especially after leaked documents showed that the Aussie government’s primary purpose for sending troops was to cozy up to the US. All the talk about eradicating weapons of mass destruction and promoting democracy was merely “mandatory rhetoric.”

However, when I was a teenager in Australia in the late‐90s, especially while visiting rural communities in Northern Queensland, the complaint I heard the most often revolved around US trade policy, specifically US tariffs on the import of Australian lamb meat. I remember riding around the bush in a ute (flatbed pickup truck) with a local farmer who was spitting mad about US tariffs and who said that the Monica Lewinsky scandal was Bill Clinton getting his just desserts for harming Aussie sheep farmers. What a thought! Australian headlines from the time were simply scathing in their critique of Clinton’s hypocrisy in signing a free trade deal with Canada and Mexico while slapping new tariffs on Australia.

Yet other than the mad cow panic, meat import policies — let alone veal tariffs, lol — have never been a major political issue in recent US national politics. But they sure mattered a great deal to Australia, which is the second largest sheep exporting country in the world (Australia and New Zealand combine for an incredible 93% of the global market). In any case, US trade policy in the 1990s fit with Australian nationalists’ broader critique of the US as a bully who simply expected Australia to meekly comply with its broader geopolitical agenda regardless of whether it was in Australia’s own national interest.

So Australians’ mixed opinions regarding the US are grounded in real, pragmatic considerations. It’s yet another situation in which our imperial entanglements and trade protectionism have provoked blowback.

It’s possible that in the future those feelings might revert towards the more US‐positive, Australasian mean given Chinese economic and military expansionism in the region. Up until now, Australia has been insulated from the downside risks of Chinese expansion — funnily enough, the intervening Indonesians have been a more significant target for Australian jingoism — while benefitting greatly as a supplier of raw materials for the post‐Mao Chinese economic miracle. Until the pandemic, Australia hadn’t experienced a recession in nearly thirty years (!).

On a more speculative note, if Noah Smith and other India boosters are correct, Australia’s role as a potential trading partner with India could matter as much for that country’s success as its trade with China has for the past three decades. Last year, Australia signed a new free trade deal with India and expects its exports to triple by 2035. And given the ongoing decoupling of global investment from the Chinese market, Australia could benefit from a major boost of foreign investment given its proximity and ties with India, Vietnam, and other high growth South and Southeast Asian markets (nicknamed “Altasia”). There’s little in the way of Australia enjoying another thirty years of torrid economic growth.

The US should forge a new, peer relationship with Australia, signaling that it takes Australia seriously as a vital regional ally rather than treating it as a junior partner in our foreign misadventures. We have a golden opportunity to do so right now. As Doug Bandow has noted, China has foolishly kicked off a trade war with Australia, and while Trump considered following suit with new tariffs on Australian exports, he was finally persuaded not to. We should take advantage of China’s mistake by expanding our 2005 free trade agreement with Australia and lower rates on agricultural products that are feeling the pinch from Chinese tariffs.

This is a crosspost from the author’s Substack. Click through and subscribe for more content on the intersection of history and policy.